Rachel Simone Weil (photo by Marjorie Becker)

When I first met Rachel Simone Weil years ago, we chatted about educational writing over lunch, talking little of our creative pursuits. As the years passed, I saw this talented artist, video game developer and design historian amass an amazing portfolio of work. Not to mention, she operates FEMICOM Museum, a celebration of femininity in the realms of 20th century video games, computing and electronic toys. When we caught up again earlier this summer, I couldn’t wait to ask her about her creative projects, as well as our shared love of ’80s design. Retro-fabulous, glitchy and ultra-feminine are all words that can be used to describe Rachel’s work. Let’s learn more about her talents…

Thank you for taking the time to chat with us, Rachel. Your aesthetic is so innovative and refreshing. Not to mention, I love the glitchy quality of your work. Can you start by telling us a little bit about what inspires you as you create your visuals?

I would describe my artistic practice as a sort of whimsical and critical reimagination of the history of computing and video games.

Many of us who grew up playing video games might see the pastime as a relatively young one whose history is well documented and understood. But as a games historian, I’ve come to see that this isn’t exactly true. We’re very good at collectively remembering and reliving the same memory over and over (Super Mario Bros., for example) while other large swaths of video game history fall away relatively unnoticed. We risk losing the traces of old games and software, especially those without contemporary remakes and licensed merchandise.

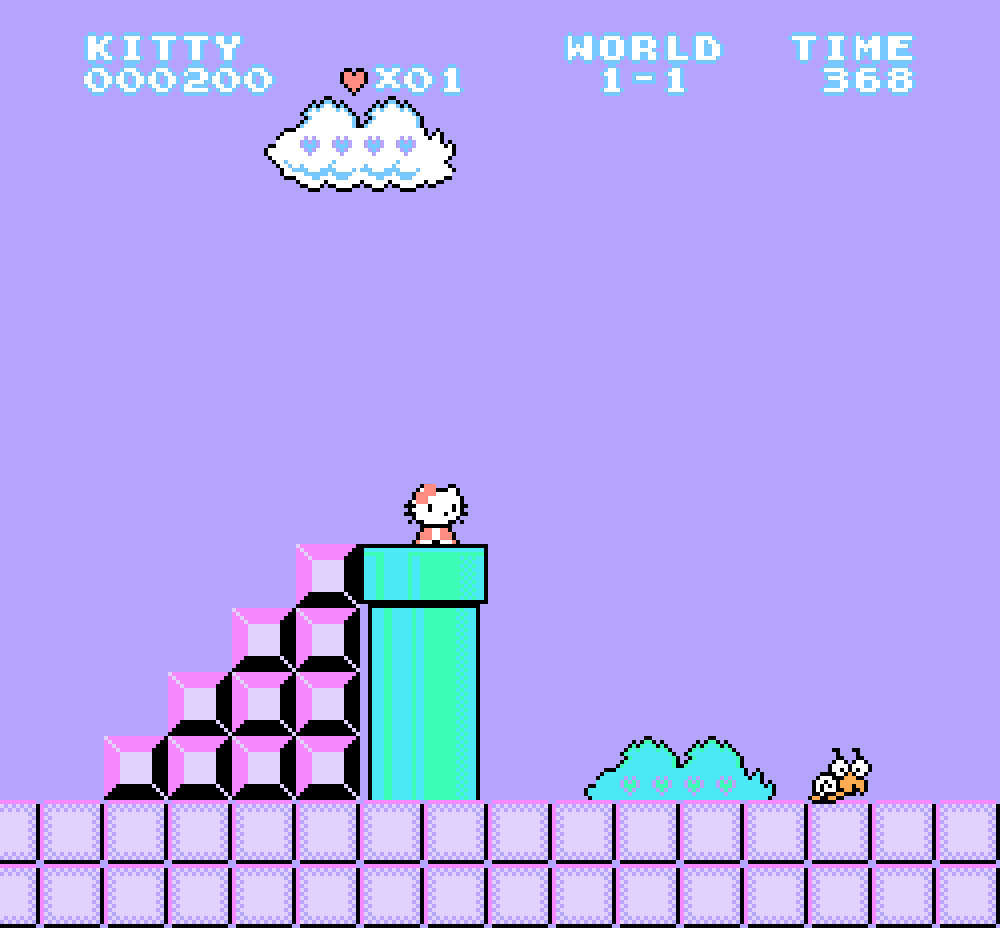

Look at Me Now, I’m Burning up the Steel by Rachel Simone Weil

One way I address this issue is in my work with FEMICOM Museum, which preserves the history of twentieth-century girly games. In my research, I discovered that documentation of girly, pink-hued video games was especially scarce and incorrect, largely due to cultural biases that deem “girl stuff” inherently inferior. Overly-cutesy, weird, art games and software are always among my favorites, and I happen to like “girl stuff,” you know, so I was rather disappointed by this and was compelled to take action.

But I’m also quite passionate about working this topic from the fine arts angle. What could video game history have looked like? What should it have looked like? I like to play with false histories, fake game artifacts, fabricated ephemera, things of that sort. For example, I create new 1980s-era NES games from scratch using authentic methods, from assembly language programming to cartridge manufacture. For me, it’s not so much a love-letter to my childhood but rather a push to better challenge the quality and breadth of our video game and software histories. I usually include glitches in my games and visual art, partially because I think the software glitch serves as a metaphor for that idea of disrupting nostalgia, of getting something you weren’t expecting or failing to get what you were promised.

I’m greatly inspired by 1980s and 1990s graphic design and commercial art from the US and Japan, whether in the form of advertisements, cartoons, package design, music videos… really any kind of popular visual media from the last two decades of the twentieth century. It’s quite interesting to observe the ways in which ideas about technology, art, and communication traveled back and forth between the US and Japan in the 1980s. Of course, many of the video games popular in the US in the late ’80s and early ’90s were coming out of Japan, so that cross-cultural aspect is relevant to what I do as a game historian and artist.

An image from Hello Kitty Land by Rachel Simone Weil

You spent the summer of 2013 in Tokyo. What differences did you notice between gaming culture in America vs. gaming culture in Japan?

Yes, my time in Tokyo was incredible. I spent a lot of time visiting arcades and toy stores, talking to game developers, and browsing the aisles at video game resale shops. It was as fun as it sounds, though I was hard at work documenting my findings. Believe it or not, I had a fairly regimented agenda every day, and I also spent a lot of time writing and photographing.

Many game enthusiasts in the US are interested in Japanese retrogaming and enjoy discovering old video games that were never translated and brought to the States. In some ways, playing these games constitutes a sort of reimagining of the past. We might ask ourselves, “Wow, what if I had played this when I was a kid?”

Party Balloons by Rachel Simone Weil

Tell us about some of your favorite games and toys as a child, including your history as a gamer if you feel like sharing!

I recall so many toys from my childhood with amazing clarity. When I wasn’t reading, my favorite pastimes were playing with Barbie dolls, collecting baseball cards, and absolutely anything related to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. My dad was very much into toys and anything collectible, so that aspect of myself was cultivated and encouraged from a young age! In addition to sports cards, I also collected Monster in My Pocket toys and seashells. I went so far as to hand-number my seashell collection, imagining that the order I’d imposed on them would be useful somehow to the museum that would some day take them in.

I didn’t have much in the way of video games or computers as a kid. My first game console (a Sega Genesis) and my first computer (some ancient IBM machine with a monochrome screen and a 5.25″ disk drive) were both obsolete hand-me-downs by the time I got them in the 1990s. I guess being into old technology was inevitable, too, huh?

Insofar as a child can be into a certain kind of aesthetic, I was enamored of the aesthetics of birthday parties and weddings: hearts, balloons, sweets, flowers, makeup, ribbons, and confetti. I liked all of those things in real life, too, I suppose, but I preferred them as decoration, as symbols for what they represented: celebration, love, and friendship. These celebratory, sweet images can be found throughout the games and visual art I create. I think they’re asking a question, which is: “Why do we denigrate and mock girly aesthetics when their visual motifs so often represent love, kindness, and joy?”

An image from Sweet-N-Fun-Fortune Teller by Rachel Simone Weil

On that note, I talk to parents today who don’t want their daughters to be too “girly”. Not to mention, there’s really been a push to foster a love of technology, math and science in girls. How do these sentiments and developments play into your desire to archive a range of feminine games, even those that reinforce female stereotypes?

Frankly, I feel a little insulted when people say that femininity is stupid or superficial. The implementation of femininity in media or commercial goods can be stupid or superficial, absolutely. But femininity itself?

A little side story: While chemistry wasn’t my best subject in grade school, I enjoyed the scientific aspect of girly craft projects I did when I was a kid, like making homemade soap, candles, and potpourri. I studied fixatives and volatiles, and I had an old tackle box retrofitted to store different kinds of dried flowers. Funnily enough, a few years later, I ended up graduating from college with a degree in chemistry and pursuing a career in candymaking. (The candymaking part didn’t happen, unfortunately, but only because I got a wonderful job opportunity in a different field.) I mention this because being girly or liking girly things does not preclude one from being smart or inquisitive or anything else. And I’m hearing that sentiment more and more lately; young women are rebelliously saying, “Hey, don’t trash what I’m into! Don’t tell me how to be!” Maybe we’re in the midst of a cultural shift.

If anything, I hope we can take some of this energy that we’re investing into girls, an energy that is well-intentioned but has grown absurd in some ways, and put that toward boys and encouraging their development, curiosity, emotional well-being, and intellectual diversity. (And yes, breaking down those social barriers that discourage them from expressing feminine traits, aspects, or interests! After all, anyone who celebrates femininity should celebrate everyone’s access to it, right?)

Faxie’s Unicorn Blast by Rachel Simone Weil

I love talking with people who are enjoying creative careers. You’re an experimental artist, a video game historian, a professor, and a self-taught assembly language programmer (to name a few talents). Not to mention, you have a blog and a podcast, and you create live visuals to accompany musical performances. Do you have any advice for others trying to carve out a creative niche and turn their talents into a rewarding career?

Ha, I have no advice to give at all! In the words of Tavi Gevinson, I’m still figuring it out.

“Don’t quit your day job” is a very cliché thing to say, but it’s also excellent advice. It sounds romantic to not care about money and throw yourself into a passion project, but it’s also incredibly unsustainable. Take care of yourself, eat well, sleep every now and again, walk around, look at antiques, visit friends, stay healthy so that you can continue to practice your craft. I know that this is good advice because I’ve repeatedly done the exact opposite.

I think also: “Tell everyone you know about the things you did as a child.” This is advice I really enjoy following, as you can undoubtedly tell, but there’s some reasoning behind it. So often, we hand over our childhood memories to people who are trying to sell us t-shirts. Not to pick on Star Wars, but how much of its current cultural celebration stems from being able to buy just about anything with the movie’s logo on it? When we purchase these objects, they convey ideas about ourselves to others, and back to ourselves, and these ideas spread and spread. So it’s good to talk about those lesser-known things from our pasts, too. It keeps them alive. And as cheesy as it sounds, I believe that it also sparks our own creativity and teaches us profound things about ourselves.

The home page of Rachel Simone Weil’s FEMICOM Museum

Are there any current or upcoming projects you’re excited about?

I’m very much looking forward to being an artist-in-residence at MASS Gallery in early August (this has been my first week). I’ll be thinking a lot about ’80s-inspired graphic and interior design during that time, so I’ll be crawling around Mirror80 for ideas, no doubt! And at the end of September, I’ll help host an annual indie video game festival here in Austin called Fantastic Arcade. The festival features strange and wonderful games from upcoming game designers, and it’s always a lot of fun.

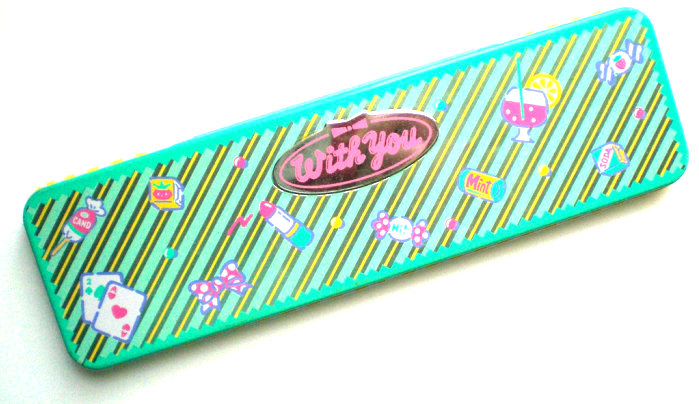

Sanrio Fresh Punch pencil tin

If you’re willing to indulge us…tell us about your favorite ’80s and ’90s…

Movies: Electric Dreams, A Girl’s Own Story (short film by Jane Campion).

Albums: Time by Electric Light Orchestra, Burning Farm by Shonen Knife.

TV shows: Jem and the Holograms, King of the Hill, Maison Ikkoku. (I think I’ve watched about every single ’90s cartoon, to be honest.)

Motifs: Confetti and analogous Memphis-esque squiggles, Sanrio’s Fresh Punch motif, which was the inspiration for my FEMICOM Museum logo.

Rachel, thank you for taking the time to chat with Mirror80. We’ve enjoyed every minute of it!

*In addition to keeping up with Rachel through her website, you can follow her on Twitter and Tumblr.

Leave a Reply